NINETEEN

1926

Friday, January 8

Graham had the day off and walked Paddy along the banks of the Trent, past the village of Wilford, towards a colliery. Clifton Grove, local legend said, was where JM Barrie had seen an urchin in rags, his inspiration for the character of Peter Pan. Barrie had worked at The Journal in the 1880s. Graham sometimes felt like one of Barrie’s lost boys. He’d been thrown out of his pram and left to fend for himself in a netherworld where he barely understood the rules.

This Christmas, he’d been home for ten days. A normal family Christmas with the welcome addition of a Catholic mass and a visit from his beloved. He felt better for the break. Paddy, however, had missed his regular walks. In Berkhamsted, Graham had been neglectful about taking him out. He’d expected other members of the family to pick up the slack. They, equally preoccupied by the festivities, had shown no interest. Paddy, consequently, played up. He’d made his mess in the house several times. Which had not made Graham popular.

In London, he’d been to see Sir Charles Starmer again, asking for a job on the Weekly Westminster Gazette. A weekly wasn’t as good as a daily but beggars can’t be choosers. The peer had forgotten that Graham was a friend of Naomi’s. Indeed, he seemed under the impression that Graham was a friend of his nephew’s, a notion that Graham did nothing to dislodge. The Gazette’s News Editor, on the other hand, was under the impression that Graham was a friend of Starmer’s. He talked about giving Graham a month’s trial on the daily, shadowing reporters covering murders, fires and other serious matters. He could also have a go at writing leaders, something the Nottingham Journal had promised. This was a promise it had yet to make good on, despite a couple of half-hearted reminders from Graham. He’d find it hard to pick up the Nottingham tone, he’d been told.

The Gazette trial, while a promising prospect, was unlikely to start before March.

‘You’ve only been in Nottingham a month!’ Starmer said, when he pushed for the trial to start earlier. Graham insisted that it was actually two and he’d already learnt all that there was to learn there. Which was true.

Today, he found the smell of freshly mined coal invigorating. They walked much further than he’d intended. By the time he returned to Ivy House, they must have walked the best part of ten miles. Paddy, exhausted, collapsed in his basket. Graham took an uncomfortable bath. The bath in Ivy House was far too short for his 6’ 2”. He was in and out in ten minutes.

Leaving the bathroom, towel wrapped around his waist, he found the landlady coming out of his sitting room.

‘Ah, there you are,’ she said, as though she had a right to be in his room whenever he wasn’t.

‘Happy new year,’ he said, conscious of the small woman inspecting his pale, all but hairless chest. She appeared to be making a judgement about his male attributes, one he would prefer not to contemplate.

‘Sally’s missed your little dog.’

‘I expect he’s missed her, too.’

‘It’s her birthday two weeks on Saturday,’ Mrs Loney said, as though this were information he required. ‘Sixteen. The boys have started sniffing round.’

She said this, with what was not exactly a wink, so much as a different kind of appraising glance, one intended to assess whether he had any interest in her daughter. Graham tried to remain innocently stony faced, although his thoughts had strayed in that direction more than once. Too close to home.

After his long walk, he badly needed a rest. He decided to treat himself to two films rather than his usual one. He made his way to The Elite on Lower Parliament Street, the smartest cinema in town, taking his seat just as the matinee of Stella Dallas was about to begin.

On a Friday afternoon the cinema was more crowded than he was used to. He found himself sat snugly between two groups of women who must just have come off shift at one of the city’s many lace works. They chatted noisily through the newsreel which was about the state of emergency in Greece, where a general had just made himself dictator. The minute the movie began, however, they gave it their full attention.

In Stella Dallas a small-town girl married a rich, older man played by Ronald Colman. Things quickly went wrong. Graham, thinking of his potential rival, Hugh, found this comforting. The second half of the story told how Stella made numerous sacrifices for the sake of her child. This interested him less. Children were not a subject he gave much thought to, one reason he had been so ill suited to teaching.

After the film, he walked down Market St to The Kardomah, meaning to ask Sally if she would look in on Paddy. But the girl was not in the crowded cafe. Back on Market Square, the pubs had just opened. There were several groups of rowdy girls in the smoky Black Boy. They’d finished work for the week and were determined to celebrate. Yet, even if Graham were to see one he liked, he’d no more idea how to peel her away from her group of pals than he had of how to persuade the girl in question to peel off her knickers.

The aging tart who sat just inside the door, with a blue rinse and a low, low top, gave him a wink.

Beyond the edge of the square was a Yates’ Wine Lodge. A single man might feel more comfortable in there. Yates’ had a cavernous ground floor. A balcony ran around its upper area, at one end of which a trio played popular songs. A tall woman with hair piled high, Victorian style, was accompanied by piano and double bass. Their repertoire was a mixture of old saws and recent hits, like the tune they were playing now, ‘Brown Eyes, Why Are You Blue?’.

The music grated on him, particularly the high-pitched squeals of the singer, impersonating an opera star. There were plenty of men on their own. Solitary drinkers sank pints at the end of a working week. Their pale faces emanated what felt to Graham like stoicism or muted despair. He did not belong here but ordered a sherry all the same. Yates’ had barrels of the good South African stuff.

Glass in hand, he found a small table on the far side from the bar, where he could observe the comings and goings unobtrusively. A woman leant over and pointed at the chair. She was a little older than him, in a loose mackintosh, with just a hint of rouge and a smear of lipstick across her pretty, if world weary face. He waited for her to say the time-honoured words the tart had used on him in Soho: looking for business? But no.

‘Is that seat free?’ she asked, with a friendly smile. Graham nodded.

‘Thanks, duck.’ She picked up the seat and took it five yards across the saloon, where she joined a group of women. A man in a white coat came by with a basket full of cockles and mussels in small jars. Graham bought a jar of cockles for twopence and ate them slowly, observing. He had never belonged in a place less.

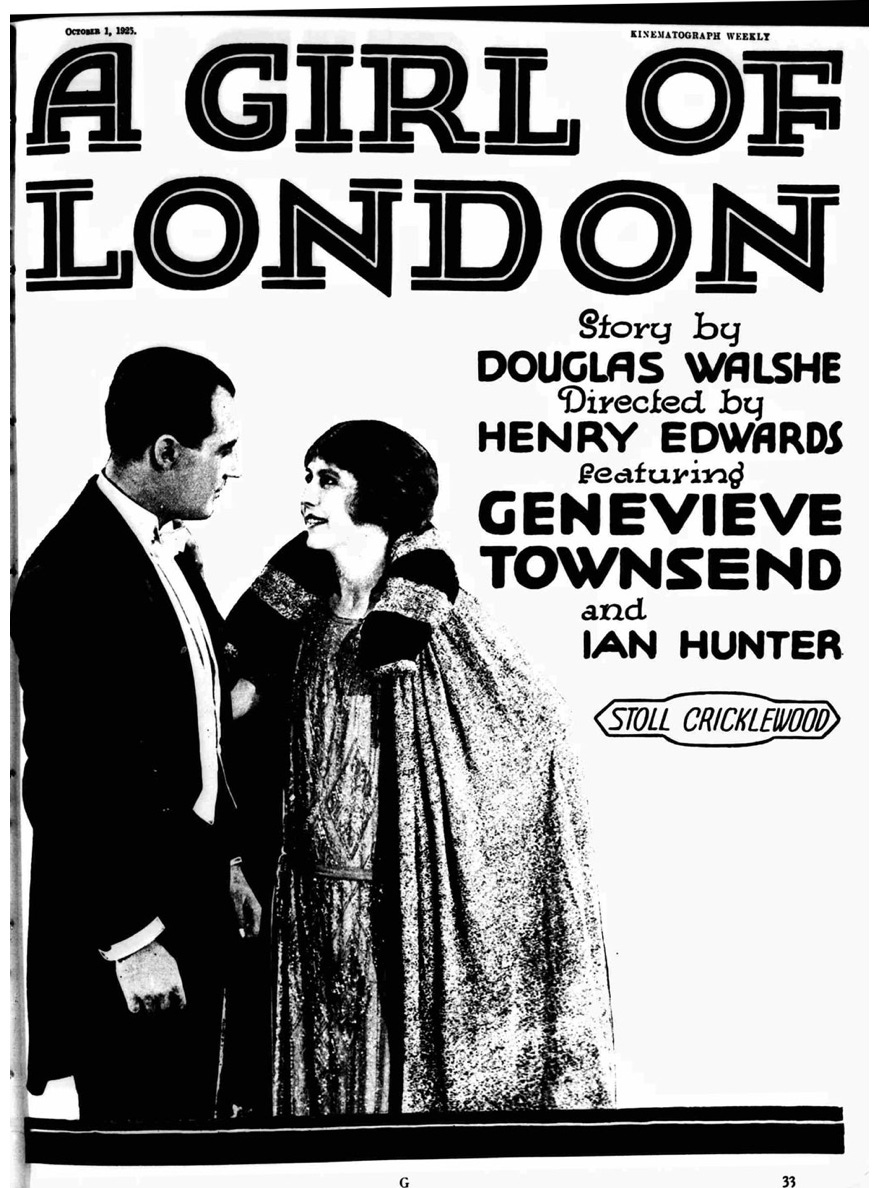

To the pictures again, then. This time he tried the Victoria Picture House opposite the railway station. A Girl of London had opened that afternoon. The old cinema was packed. The Victoria turned out to have a semi-circular balcony at the rear. It only held ten or so people, but he spotted a free seat. This was the first cinema outside London where Graham had found ice cream on sale, so he treated himself to a small tub before climbing the short spiral staircase to the balcony, where he again sat between two groups of excitable factory girls.

The film wasn’t bad. Genevieve Townsend, the brunette who played the girl of the title, had a look of Vivienne to her, which pleased him, though she was rather flat chested. The story was of a type becoming familiar. The hero was the son of a Tory MP who fell in love with a factory girl and married her. Consequently, his father disowned him. The tale turned to the hero’s attempt to rescue his new wife from the influence of her stepfather, who ran a drugs den. This all seemed unlikely and stupidly melodramatic to Graham. Still, the audience lapped it up, with plenty of laughter, encouraging interjections and loud curses for the villains. Presumably, in Nottingham, they reckoned London was full of drug dens.

When he got home there was still a light on in Sally’s room. What was she doing up so late? She could only be waiting for him. Don’t flatter yourself, he thought, then had to remind himself that she was still only fifteen. If he wanted release, he could walk to the Lace Market, where, he’d heard subs say, there were girls who’d suck you off in the public toilets for ten shillings or do anything else you required for another half a crown, but make sure you took a condom if you didn’t want a dose. On the Forest, another sub had told him, there were boys who offered a corresponding service, up against the trees.

He was in the habit of using the WC before he went to bed, careless of whether the loud, clanking flush disturbed anyone’s sleep. But tonight he had a feeling the girl might be waiting for him. Rather than risk an ‘accidental’ encounter on the landing, he used the chamber pot. All night its sour sweet odour drifted up to his bed.

The film A Girl of London was released in September, 1925. All copies are thought lost.

Happy New Year. Thanks for reading Greeneland. The next chapter will appear on Sunday.

If you’re enjoying the novel, please tell your friends about it in whatever way suits you best. Word of mouth is by far the best recommendation.